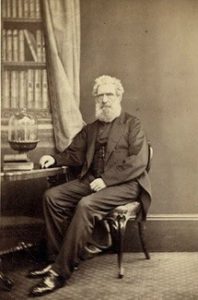

DOUGLAS, James (1800-1886)

Biography

Born on May 20th 1800 in Brechin, Scotland, James Douglas was the son of George Douglas, Methodist minister, and of Mary Mellis.

In 1813, Douglas began a medical apprenticeship under a doctor in Penrith, England. In 1818, he studied surgery at the Edinburgh School of Medecine. A year later, he worked as a surgeon on a whaling ship before returning to his studies at the Edinburgh College of Surgeons, and at the London College of Surgeons.

Douglas practiced medicine for a year in India and, upon returning to the UK in 1822, he accepted the direction of medical services for a new colony being set up in Honduras. After this colonial experiment failed in 1823, he was sent to Boston to receive treatment for Yellow Fever. He lived for several years in central New York, where he set up a medical practice and taught at the Auburn Medical College.

During the winter of 1825-1826, Douglas was forced to flee the United States to avoid being arrested for the illegal dissection of two stolen cadavers. He settled down in Quebec City, where he worked in rooms provided by Doctor Joseph Painchaud.

In 1837, Douglas became head doctor and director of the Marine and Emigrant Hospital in Quebec City. In the early years of his direction, the hospital gained a positive reputation and provided teaching that was both recognized and appreciated by the medical and academic sectors.

In 1845, the governor asked Douglas to develop a strategy for housing and curing the insane disseminated throughout the province, that were often locked up in deplorable conditions. The Beauport Lunatic Asylum opened up that same year. Little by little, Douglas neglected his work at the Marine and Emigrant Hospital for the Asylum. The hospital slowly deteriorated and Douglas’ leadership was severely criticized during a royal enquiry in 1852.

Suffering from respiratory problems, Douglas spent his winters abroad as of 1850, including numerous stays in Egypt. He accumulated an important collection of mummies and objects from ancient Egypt, which were donated or sold to museums. One of these mummies was repatriated to Egypt in 2003 after it was discovered to be King Ramses I. Douglas and his son were also among the first to photograph the monuments of Egypt, and their photos are now recognized as important documents in the early history of photography.

Douglas invested a considerable amount of time and energy in the development of copper mines in Quebec. He founded mining companies in Inverness, Quebec and at the Harvey Hill Mine in Saint-Pierre-de-Broughton, remaining the majority stakeholder in both these operations. Despite a promising start, the discovery of sterile veins and the lack of financial resources led to the sale of his mining operations.

Douglas went to Europe in 1865 and his son sold all his assets. In 1875, he moved with his son to Phoenixville, Pennsylvania.

He was the author of An account of the attempt to form a settlement on the Mosquito Shore in 1823 (1869), A whaling voyage to Spitzbergen in 1818 (1873) and of the Journals and reminiscences of James Douglas (posthumous, 1910).

He died in New York on April 14th 1886. He is buried at Mount Hermon Cemetery in Québec.

He married Hannah Williams in Utica, New York in 1824. He then married Elizabeth Ferguson, daughter of Archibald Ferguson, in Quebec City in 1831. He was the father of James Douglas, mining tycoon.

– Patrick Donovan, June 2015

Bibliography

- GRAHAM, Jennifer. “Photographic views taken in Egypt and Nubia by James Douglas M.D. and James Douglas Jr.” Master’s Thesis, Ryerson University and George Eastman House : International Museum of Photography and Film, 2014.

- LEBLOND, Sylvio. “Douglas, James.” Canadian Encyclopedia [online]. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/

- LEBLOND, Sylvio. “Douglas, James.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography [online]. http://www.biographi.ca/

- MAYELL, Hillary. “U.S. Museum to Return Ramses I Mummy to Egypt.” National Geographic News, 2003. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2003/04/0430_030430_royalmummy.html